1 Introduction

For me, the best way to learn something is to do it by explaining it to other people.

With this in mind, I decided to make a website which supports blog posts so that I

can document what I’m learning about. So you’ll be pretty much learning together

with me. One of the things I was really excited about learning was category

theory.

My motivation for that is the use of category theory in machine learning. Maybe

I’ll do some category theory notes on machine learning later.

I’ll be using Tom Leinster’s book “Basic Category Theory” (available at

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1612.09375) as a guide, and I’ll be following it

closely. I’ll also try to introduce some of my own ideas/some stuff I find

online.

For now, I’ll only put the statements of some theorems/lemmas/exercises. This is

more of a reference for me. Treat this material as a draft. I’ll be updating it as I learn

more. Also, it is more of a summary of the subject than actual detailed

notes.

So without further ado, let’s begin.

1.1 Why study category theory?

From a pure mathematics point of view, category theory is a unifying theory. It

provides a common language for discussing problems in different branches of

mathematics. It also provides a way to abstract away the details of a problem and

focus on the essential structure of the problem.

It’s kind of a bird’s eye view of mathematics.

2 Categories

Definition 2.1. A category \(\cat{A}\) consists of:

-

1.

- a collection \(\catobj{A}\) of objects;

-

2.

- for each \(A, B \in \catobj{A}\), a collection \(\catmor{A}{A}{B}\) of maps or arrows or morphisms from \(A\) to \(B\);

-

3.

- for each \(A, B, C \in \catobj{A}\), a function \begin{align*} \catmor{A}{B}{C} \times \catmor{A}{A}{B} & \to \catmor{A}{A}{C} \\ (f, g) & \mapsto f \circ g \end{align*}

called composition.

-

4.

- for each \(A \in \catobj{A}\), an element \(1_A \in \catmor{A}{A}{A}\), called the identity on \(A\)

satisfying the following axioms:

-

1.

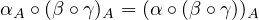

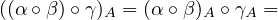

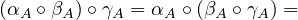

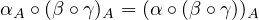

- associativity: for each \(A, B, C, D \in \catobj{A}\) and each \(f \in \catmor{A}{C}{D}\), \(g \in \catmor{A}{B}{C}\) and \(h \in \catmor{A}{A}{B}\), \((f \circ g) \circ h = f \circ (g \circ h)\).

-

2.

- identity laws: for each \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{B}\), we have \(f \circ 1_A = f = 1_B \circ f\)

Example 2.2. The category \(\textbf{Set}\) has sets as objects and functions as morphisms.

Composition is the usual composition of functions.

Example 2.3. The category \(\textbf{Grp}\) has groups as objects and group homomorphisms

as morphisms. Composition is the usual composition of functions.

Example 2.4. The category \(\textbf{Top}\) has topological spaces as objects and continuous

functions as morphisms. Composition is the usual composition of functions.

Example 2.5. The category \(\textbf{Vect}_K\) has vector spaces over a field \(K\) as objects and

linear maps as morphisms. Composition is the usual composition of functions.

Example 2.6. The category \(\textbf{Pos}\) has partially ordered sets as objects and

order-preserving functions as morphisms. Composition is the usual composition

of functions.

Example 2.7. The category \(\cat{C}\) whose objects are natural numbers and for each

\(a \leq b \in \catobj{C}\), \(\catmor{C}{a}{b}\) contains exactly one element, namely the assertion that \(a \leq b\). We define the

composition of assertions \(a \leq b\) and \(b \leq c\) as the assertion \(a \leq c\).

Remark 2.8. We can think of a group \(G\) as a category with one object and

all elements of \(G\) as morphisms. The composition of morphisms is the group

operation.

Definition 2.9. Every category \(\cat{A}\) has an opposite or dual category \(\cat{A}^{op}\), which has

the same objects as \(\cat{A}\) but has \(\catmor{A^{op}}{A}{B} = \catmor{A}{B}{A}, \, \forall A, B \in \catobj{A}\) i.e. the arrows are reversed.

Definition 2.10. Given categories \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\), there is a product category \(\cat{A} \times \cat{B}\), in which \begin{align*} \catobj{\cat{A} \times \cat{B}} & = \catobj{A} \times \catobj{B} \\ (\cat{A} \times \cat{B})((A, B), (A', B')) & = \catmor{A}{A}{A'} \times \catmor{B}{B}{B'} \end{align*}

Rigorously, this isn’t quite complete. You still need to define composition and

identities. However, there is only one sensible way to do this here.

Proposition 2.11. A map in a category can have at most one inverse. That

is, given a nonempty category \(\cat{A}\) and objects \(A, B \in \catobj{A}\), then for each \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{B}\), there exists at most

one \(g \in \catmor{A}{B}{A}\) such that \(f \circ g = 1_B\) and \(g \circ f = 1_A\).

Proof

Suppose \(g\) and \(g'\) are inverses of \(f\). Then \(g = g \circ 1_B = g \circ (f \circ g') = (g \circ f) \circ g' = 1_A \circ g' = g'\). \(\blacksquare \)

Definition 2.12. Let \(\cat{A}\) be a category and \(A, A' \in \cat{A}\). If there exists some morphism \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\) s.t.

\(f\) has an inverse \(g\), we say that \(f\) is an isomorphism from \(A\) to \(A'\). Moreover, we say

that the objects \(A\) and \(A'\) are isomorphic and write \(A \cong A'\).

3 Functors

Definition 3.1. Let \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) be categories. A functor \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) consists of:

-

1.

- A function \(\catobj{A} \to \catobj{B}\) written as \(A \mapsto F(A)\)

-

2.

- for each \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}\), a function \(\catmor{A}{A}{A'} \to \catmor{B}{F(A)}{F(A')}\) written as \(f \mapsto F(f)\), satisfying the following axioms

-

(a)

- For all \(A, B, C \in \catobj{A}\), \(f \in \catmor{A}{B}{C}\), \(g \in \catmor{A}{A}{B}\), \(F(f \circ g) = F(f) \circ F(g)\)

-

(b)

- For all \(A \in \catobj{A}\), \(F(1_A)=1_{F(A)}\)

Example 3.2. The identity functor preserves everything about the category.

It’s not even fun to be considered.

Example 3.3. The easiest non trivial functors are the forgetful functors.

There’s really no formal definition of this term, though. It’s just the name given

to a functor which forgets some underlying structure. For example, the functor \(F : \textbf{Grp} \to \textbf{Set}\)

which maps each group to its underlying set and each group homomorphism to

its underlying function is a forgetful functor.

Definition 3.4. Let \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) be categories. A contravariant functor from \(\cat{A}\) to \(\cat{B}\) consists

of:

-

1.

- A function \(\catobj{A} \to \catobj{B}\) written as \(A \mapsto F(A)\)

-

2.

- for each \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}\), a function \(\catmor{A}{A}{A'} \to \catmor{B}{F(A)}{F(A')}\) written as \(f \mapsto F(f)\), satisfying the following axioms

-

(a)

- For all \(A, B, C \in \catobj{A}\), \(f \in \catmor{A}{B}{C}\), \(g \in \catmor{A}{A}{B}\), \(F(f \circ g) = F(g) \circ F(f)\)

-

(b)

- For all \(A \in \catobj{A}\), \(F(1_A)=1_{F(A)}\)

i.e. the same as a normal (or covariant) functor from \(\cat{A}\) to \(\cat{B}\) except for the composition

axiom, which is now inverted.

Remark 3.5. When we defined functors and contravariant functors, all we said

is that they ”consist of a list of things”. This allows us to regard a contravariant

functor from \(\cat{A}\) to \(\cat{B}\) as simply a (covariant) functor from \(\cat{A}^{op}\) to \(\cat{B}\). Or even a functor

from \(\cat{A}\) to \(\cat{B}^{op}\). I leave checking that this is indeed the case to the reader.

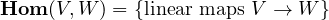

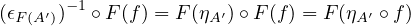

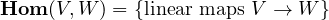

Example 3.6. Let \(K\) be a field. For any two vector spaces \(V\) and \(W\) over \(K\), there is

a vector space

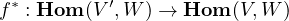

Fixing \(W\), any linear map \(f : V \to V'\) induces a linear map

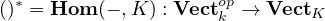

defined at \(q \in \textbf{Hom}(V', W)\) by \(f^*(q) = q \circ f\). This defines a functor \(\textbf{Hom}(-, W) : \textbf{Vect}^{op}_K \to \textbf{Vect}_K\) i.e. a contravariant functor from the

category of vector spaces over \(K\) to itself.

Indeed, given \(V \in \textbf{Vect}^{op}_K\), \(\textbf{Hom}(-, W)(V) = \textbf{Hom}(V, W) \in \textbf{Vect}_K\). Also, if \(f\) is a morphism in \(\textbf{Vect}^{op}_K\) from \(V'\) to \(V\) (i.e. a linear map from \(V\)

to \(V'\)), then the aforementioned induced map \(f^{*}\) from \(\textbf{Hom}(V', W) \to \textbf{Hom}(V, W)\) is the morphism which is the

output of the functor with input \(f\).

For completion, notice that the identity map \(f : V \to V\) corresponds to the induced

map \(f^*\) which maps each \(q \in \textbf{Hom}(V, W)\) to \(q \circ f = q\) (i.e. the identity map on \(\textbf{Hom}(V, W)\)). Also, if \(f : V_1 \to V_2\), \(g : V_2 \to V_3\) are morphisms

in \(\textbf{Vect}^{op}_K\), then we’re talking about the linear transformations \(f' : V_2 \to V_1\) and \(g' : V_3 \to V_2\). We have that

\((g \circ f)' = f' \circ g' : V_3 \to V_1\). The induced map of this composition is the one which maps some \(q\) to \(q \circ f' \circ g'\). The

induced maps to \(g'\) and \(f'\) are the ones that map \(q\) to \(q \circ g'\) and \(q \circ f'\), respectively. So the

composition of these maps evaluated at \(q\) first map \(q\) to \(q \circ f'\) and then to \(q \circ f' \circ g'\). So the

composition law holds and we indeed have a functor.

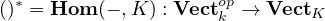

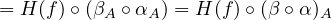

Remark 3.7. If we set \(W=K\) (seen as a one dimensional vector space over itself)

we get an important special case. We call \(\textbf{Hom}(V, K)\) the dual of \(V\) and is written as \(V^*\). So

there is a contravariant functor

sending each vector space to its dual.

Definition 3.8. Let \(\cat{A}\) be a category. A presheaf on \(\cat{A}\) is a functor \(\cat{A}^{op} \to \textbf{Set}\) i.e. it’s a

contravariant functor from \(\cat{A}\) to \(\textbf{Set}\).

Example 3.9. Let \(X\) be a topological space, and let \(\cat{O}(X)\) be the category whose

objects are open sets of \(X\) and whose morphisms are inclusions. Then a presheaf

on \(X\) is a contravariant functor \(F\) from \(\cat{O}(X)\) to \(\textbf{Set}\). We can define this functor in such a

way that \(F(U) = \{\text{continuous functions } U \to \mathbb{R} \}\).

Notice that if \(U \subset V\) are open sets, then since there’s an unique morphism from \(U\) to

\(V\) on \(\cat{O}(X)\), then there’s an unique morphism from \(F(V)\) to \(F(U)\). We can define this morphism

as the restriction of functions.

Definition 3.10. A functor \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) is faithful (resp. full) if for each \(A, A' \in \cat{A}\), the function \begin{align*} \catmor{A}{A}{A'} & \to \catmor{B}{F(A)}{F(A')} \\ f & \mapsto F(f) \end{align*}

is injective (resp. surjective).

Definition 3.11. Let \(\cat{A}\) be a category. A subcategory \(\cat{S}\) of \(\cat{A}\) is a category such that

its objects \(\catobj{S}\) are a subclass of \(\catobj{A}\) and for each \(S, S' \in \catobj{S}\), \(\catmor{S}{S}{S'}\) is a subclass of \(\catmor{A}{S}{S'}\) which is closed

under compositions and identities. It is a full subcategory if \(\catmor{S}{S}{S'} = \catmor{A}{S}{S'}\) for all \(S, S' \in \catobj{S}\).

Remark 3.12. A full subcategory can be specified only by specifying its

elements. For example, \(\textbf{Ab}\) is a full subcategory of \(\textbf{Grp}\).

Proposition 3.13. Let \(\cat{S}\) be a subcategory of \(\cat{A}\). Then, the inclusion functor \(I : \cat{S} \to \cat{A}\) is

faithful. Additionally, it’s full if and only if \(\cat{S}\) is a full subcategory of \(\cat{A}\).

Proof

Trivial. Let \(S, S' \in \catobj{S}\) and \(f_1, f_2 \in \catmor{S}{S}{S'}\). Then, \(I(f_1) = I(f_2) \implies f_1 = f_2\).

Additionally, suppose \(I\) is full. Then, \(I(\catmor{S}{S}{S'})=\catmor{A}{I(S)}{I(S')}=\catmor{A}{S}{S'}\). But \(I(\catmor{S}{S}{S'}) = \catmor{S}{S}{S'}\) since \(I\) is the inclusion map. Hence, \(\catmor{A}{S}{S'} = \catmor{S}{S}{S'}\), as

desired.

Conversely, suppose \(\cat{S}\) is full. Then, \(I(\catmor{S}{S}{S'})=\catmor{S}{S}{S'}=\catmor{A}{S}{S'}=\catmor{A}{I(S)}{I(S')}\), which proves \(I\) is also full. \(\blacksquare \)

Remark 3.14. Let \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) be categories and let \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) be a functor. Then, it is not

necesssary that the image of \(F\) is a subcategory of \(\cat{B}\). Can you prove that by

providing an example?

Proof

Suppose \(A, B, B', C \in \catobj{A}\) s.t. \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{B}\), \(g \in \catmor{A}{B'}{C}\). Let \(X=F(A), Y=F(B)=F(B'), Z=F(C)\), \(p=F(f), q = F(g)\). Then \(p, q\) are in the image of \(F\) but \(q \circ p\) is not (necessarily).

\(\blacksquare \)

Proposition 3.15. Functors preserve isomorphisms. That is, if \(F:\cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) is a functor

and \(A, B \in \catobj{A}\) s.t. \(A \cong B\), then \(F(A) \cong F(B)\).

Proof

From the isomorphisms, there exist \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{B}, g \in \catmor{A}{B}{A}\) s.t. \(f \circ g = 1_A\) and \(g \circ f = 1_B\). Applying \(F\) at both sides of these

equalities, we get \(F(f) \circ F(g) = 1_{F(A)}\) and \(F(g) \circ F(f) = 1_{F(B)}\) where \(F(f) \in \catmor{A}{F(A)}{F(B)}\) and \(F(g) \in \catmor{A}{F(B)}{F(A)}\). Hence, \(F(A) \cong F(B)\). \(\blacksquare \)

Exercise 3.16. Let \(A\) and \(B\) be preordered sets (i.e. a set with a preorder, which

is a refletive and transitive binary operation). Let \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) be the corresponding

categories (i.e. the category whose elements are the elements of the preordered

set and whose morphisms are the relations in the preorder).

Show that each functor \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) corresponds to an order-preserving map \(f : A \to B\) are

vice-versa.

Proof

Let \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) be a functor. Define \(f\) as \(f(a)=F(a)\) (\(a \in A\)). Now, let \(a_1, a_2 \in A\) with \(a_1 \leq a_2\). Notice that \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) map to \(F(a_1)\) and \(F(a_2)\),

respectively. Also, there’s an unique morphism from \(F(a_1)\) to \(F(a_2)\), namely \(F(a_1 \leq a_2)\). But by definition

of \(\cat{B}\), if such a morphism exists, it its equal to the assertion that \(F(a_1) \leq F(a_2)\), which means that \(f(a_1) \leq f(a_2)\),

which proves \(f\) is order-preserving.

Now, let \(f : A \to B\) be an order-preserving map. Define \(F\) as \(F(a)=f(a)\) (\(a \in A\)) and \(F(a_1 \leq a_2) = f(a_1) \leq f(a_2)\) (\(a_1, a_2 \in A\) s.t. \(a_1 \leq a_2\)). Clearly \(F\) is a

functor. \(\blacksquare \)

Exercise 3.17. Is there a functor \(Z : \textbf{Grp} \to \textbf{Grp}\) with the property that \(Z(G)\) is the centre of \(G\) for

each group \(G\)?

Proof

Well, yeah. Just take the image of a morphism between \(G\) and \(H\) to be simply it’s

restriction to \(Z(G)\) if its an isomorphism (verify that the image of \(Z(G)\) is precisely

\(Z(H)\) so we have an isomorphism between these two centres) and \(g \mapsto e_H\) otherwise.

\(\blacksquare \)

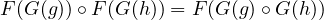

Exercise 3.18. The composition of functors (defined the obvious way) is a

functor. Moreover, functor composition is associative.

Proof

Let \(\cat{A}, \cat{B}, \cat{C}, \cat{D}\) be categories, \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\), \(G : \cat{B} \to \cat{C}\), \(H : \cat{C} \to \cat{D}\) be functors.

For the composition, the obvious definition is so that \(G \circ F\) sends \(A \in \catobj{A}\) and a functor \(f\) in \(\cat{A}\) to \(G(F(A))\)

and \(G(F(f))\), respectively. We need to prove that \(G \circ F\) satisfies the definition of a functor from \(\cat{A}\) to

\(\cat{C}\).

For this, let \(A, A', A'' \in \catobj{A}\), \(f \in \catmor{A}{A'}{A''}\), \(g \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\). Now, \((G \circ F)(f \circ g) = G(F(f \circ g)) = G(F(f) \circ F(g)) = G(F(f)) \circ G(F(g))\) \(= (G \circ F)(f) \circ (G \circ F)(g)\).

Also, if \(A \in \catobj{A}\), we have \((G \circ F)(1_A) = G(F(1_A)) = G(1_{F(A)}) = 1_{G(F(A))} = 1_{(G \circ F)(A)}\). So \(G \circ F\) is a functor.

For the associativity, we just need to prove that the functors \((H \circ G) \circ F\) and \(H \circ (G \circ F)\) coincide

at every object and morphism from \(\cat{A}\). But this is equivalent to proving the

associativitiness of functions under composition, which we know it’s true.

\(\blacksquare \)

Definition 3.19. We can form the category \(\textbf{CAT}\) of all categories. The objects of \(\textbf{CAT}\)

are categories and the morphisms are functors. It’s trivial to see why this indeed

forms a category.

Definition 3.20. Two categories are said to be isomorphic if they are

isomorphic when seen as objects of \(\textbf{CAT}\).

4 Natural transformations

Definition 4.1. Let \(F, G : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) be functors. A natural transformation \(\alpha : F \to G\) is a family of

morphisms \( \alpha _A \in \catmor{B}{F(A)}{G(A)}\) (\(A \in \catobj{A}\)) such that for each \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}\) and each \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\), \(\alpha _{A'} \circ F(f) = G(f) \circ \alpha _A\). The maps \(\alpha _A\) are called the

components of \(\alpha \).

Exercise 4.2. Let \(\cat{A}\) be a discrete category (whose morphisms are only the

identities) and \(\cat{B}\) any category. Let \(F, G : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) be any functors. Show that for any family of

morphisms \(\alpha _A \in \catmor{B}{F(A)}{G(A)}\), \(\alpha : F \to G\) is a natural transformation.

Proof

Let \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}\) and \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\). Then, \(A=A'\) and \(f=1_{A}\). Thus, \(F(f)=1_{F(A)}\) and \(1_{G(A)}=G(f)\), so that \(\alpha _{A'} \circ F(f) = \alpha _{A'} \circ 1_{F(A)} = \alpha _{A'}\) \(= \alpha _{A} = 1_{G(A)} \circ \alpha _{A} = G(f) \circ \alpha _{A}\). \(\blacksquare \)

Example 4.3. Fix a positive integer \(n\). For any commutative ring \(R\), the matrices

\(M_n(R)\) form a monoid. Moreover, any ring homomorphism \(R \to S\) induces a monoid

homomorphism \(M_n(R) \to M_n(S)\). This defines a functor \(M_n : \textbf{CRing} \to \textbf{Mon}\) from the category of commutative rings

to the category of monoids.

Also, the elements of any ring \(R\) form a monoid \(U(R)\) under multiplication, giving

another functor \(U : \textbf{CRing} \to \textbf{Mon}\).

Now, every \(n \times n\) matrix \(X\) over a commutative ring \(R\) has determinant \(\det _R(X)\) i.e. each \(R\)

gives a mapping \(\det _R : M_n(R) \to U(R)\).

Prove that \(\det : M_n \to U\) is a natural transformation.

Proof

Let \(R, R' \in \textbf{CRing}\) and let \(f : R \to R'\) be a ring homomorphism. Then, \(M_n(f)\) applies \(f\) entry-wise on a \(n \times n\)

matrix and \(U(f)\) applies \(f\) to an element of \(U(R)\) when seen as an element of \(R\). Now, let

\(M \in M_n(R)\).

Notice that when we apply \(det_{R'}\) to \(M_n(f)(M)\) when using thei Leibniz formula for the

determinant, we can use the homomorphism properties of \(f\) ”in reverse” so that we

have \(f\) of a sum of products. But this sum of products is the determinant of a

matrix with entries in \(R\). More precisely, we get \(f(\det _R(M))\). But \(\det _R(M) \in R \subset U(R)\). So this can be seen as

\(U(f)(\det _R(M))\).

So we have proved \(\det _{R'} \circ M_n(f) = U(f) \circ \det _R\). \(\blacksquare \)

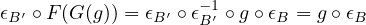

Exercise 4.4. The composition of natural transformations is a natural

transformation. More precisely, let \(\cat{A}, \cat{B}\) be categories \(F, G, H : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) be functors, and \(\alpha : F \to G\), \(\beta : G \to H\) be natural

transformations. Then, \(\beta \circ \alpha : F \to H\) (defined as \((\beta \circ \alpha )_A = \beta _A \circ \alpha _A\)) is a natural transformation.

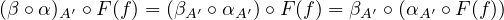

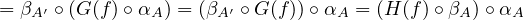

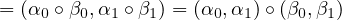

Proof

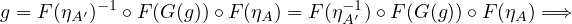

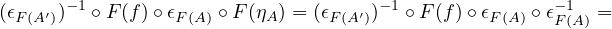

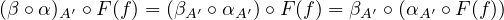

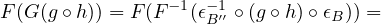

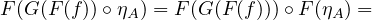

Let \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}, f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\). Then, using the associativiness of morphisms together with the facts that \(\alpha , \beta \)

are natural transformations, we have:

\(\blacksquare \)

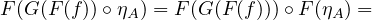

Exercise 4.5. Let \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) be categories. Construct (in a reasonable way) a

category \(\cat{C}\) whose objects are functors from \(\cat{A}\) to \(\cat{B}\) and whose morphisms are the

natural transformations. If you’ve constructed it correctly, then you ended up

with what we call \([\cat{A}, \cat{B}]\) or \(\cat{B}^\cat{A}\).

Proof

Let \(F, G, H\) be objects of \(\cat{C}\), \(\alpha : G \to H\) and \(\beta : F \to G\) be natural transformtions. Then, \(\alpha \circ \beta \) was defined

previously and we proved it’s a natural transformation from \(F\) to \(H\).

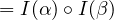

For each functor (object of \(\cat{C}\)) \(F\), we define it’s identity morphism as the natural

transformation \(\pi ^F : F \to F\) for which \(\pi ^F_A : F(A) \to F(A)\) is the identity morphism for every \(A\) i.e. \(\pi ^F_A = 1_{F(A)}\). (we need to check

that this is indeed a natural transformation. For this, simply take \(A, A' \in \cat{A}\), \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\). We have

\(\pi ^F_{A'} \circ F(f) = 1_{F(A')} \circ F(f) = F(f) = F(f) \circ 1_{F(A)} = F(f) \circ \pi ^F_A\)).

Let \(F, G\) be objects of \(\cat{C}\) and \(\alpha : F \to G\) a natural transformation. Then, \(\alpha \circ \pi ^F\) is a natural

transformation from \(F\) to \(G\). In particular, \((\alpha \circ \pi ^F)_A = \alpha _A \circ \pi ^F_A = \alpha _A \circ 1_{F(A)} = \alpha _A\). This means that \(\alpha \circ \pi ^F = \alpha \). Simmilarly, one can prove

that if \(\beta : G \to F\) is a natural transformation, then \(\pi ^F \circ \beta = \beta \).

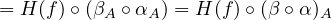

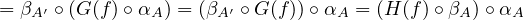

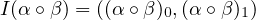

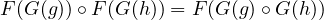

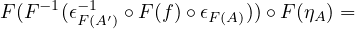

Finally, if \(F, G, H, I\) are objects of \(\cat{C}\), \(\alpha : H \to I\), \(\beta : G \to H\), \(\gamma : F \to G\) are natural transformations, then \((\alpha \circ \beta ) \circ \gamma \) and \(\alpha \circ (\beta \circ \gamma )\) are natural

transformations from \(F\) to \(I\), but are they equal? To check equality, we just need to

check if for each \(A \in \catobj{A}\), the morphisms they map to in \(\cat{B}\) coincide:

so

they are indeed equal. \(\blacksquare \)

Example 4.6. Let \(2\) be the discrete category with two objects. Then, \([2, \cat{B}] \cong \cat{B} \times \cat{B}\).

Proof

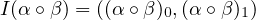

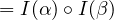

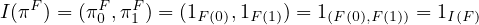

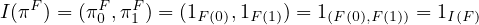

The following \(I \in \textbf{Cat}([2, \cat{B}], \cat{B} \times \cat{B})\) is an isomorphism: \(I(F) = (F(0), F(1))\) where \(F\) is an object of \([2, \cat{B}]\) (and hence a functor

from \(2\) to \(\cat{B}\)). Also, if \(\alpha \) is a morphism between objects of \([2, \cat{B}]\) (i.e. a natural transformation

between functors \(F, G : 2 \to \cat{B}\)), we can map \(\alpha \) to \(I(\alpha ) = (\alpha _0, \alpha _1)\) where \(\alpha _0\) is the morphism from \(F(0)\) to \(G(0)\) and \(\alpha _1\) is the

morphism from \(F(1)\) to \(G(1)\).

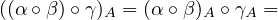

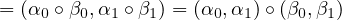

Now, \(I\) is clearly a morphism in \(\textbf{Cat}\), since it’s a functor from \([2, \cat{B}]\) to \(\cat{B} \times \cat{B}\). Indeed, let \(F, G, H \in [2, \cat{B}]\), \(\alpha : G \to H\), \(\beta : F \to G\). We

have:

Also, if \(F \in [2, \cat{B}]\) and \(\pi ^F\) is the identity morphism, we have

Now, let \(J \in \textbf{Cat}(\cat{B} \times \cat{B}, [2, \cat{B}])\) be defined as: if \((B, C) \in \cat{B} \times \cat{B}\), \(J(B, C)\) is the functor which maps \(0\) to \(B\) and \(1\) to \(C\). Also, if \((\beta , \gamma )\) is a

morphism between objects of \(\cat{B} \times \cat{B}\), \(J(\beta , \gamma )\) is the natural transformation which maps \(0\) to

\(\beta \) and \(1\) to \(\gamma \). We can also prove that \(J\) is indeed a morphism in \(\textbf{Cat}\). But that’s

too tedious. So we’ll jump straight to the part where we prove \(I\) and \(J\) are

inverses.

Let \((B, C) \in \cat{B} \times \cat{B}\). Then, \((I \circ J)(B, C)=I(J(B, C))=(J(B, C)(0), J(B, C)(1)) =(B, C)\). Also, if \((f, g)\) is a morphism in \(\cat{B} \times \cat{B}\), then \((I \circ J)((f, g))=I(J(f, g))=(J(f, g)_0, J(f, g)_1) = (f, g)\). This means that the morphism \(I \circ J \in \textbf{Cat}(\cat{B} \times \cat{B}, \cat{B} \times \cat{B})\),

which is a functor between this category, and itself coincides with the identity

functor, so that \(I \circ J = 1_{\cat{\beta } \times \cat{\beta }}\).

Simmilarly, let \(F \in [2, \cat{B}]\). Then, \((J \circ I)(F)=J(I(F))=J(F(0), F(1))=J(F(0), F(1))=F\). Also, if \(\alpha \) is a morphism in \([2, \cat{B}]\), then \((J \circ I)(\alpha )=J(I(\alpha ))=J(\alpha _0, \alpha _1)=\alpha \). This means that

\(J \circ I = 1_{[2, \cat{B}]}\).

\(\blacksquare \)

Definition 4.7. Let \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) be categories. A natural isomorphism between

functors from \(\cat{A}\) to \(\cat{B}\) is an isomorphism in \([\cat{A}, \cat{B}]\). We say that these functors are naturally

isomorphic and write \(F \cong G\).

Lemma 4.8. Let \(\cat{A}, \cat{B}\) be categories, \(F, G : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) be functors and \(\alpha : F \to G\) a natural transformation.

Then \(\alpha \) is a natural isomorphism iff \(\alpha _A : F(A) \to G(A)\) is an isomorphism for all \(A \in \cat{A}\).

Proof

Suppose \(\alpha \) is a natural isomorphism. Then, there exists a natural transformation \(\beta : G \to F\)

such that \(\alpha \circ \beta = 1_G\) and \(\beta \circ \alpha = 1_F\).

Let \(A \in \cat{A}\) and \(\alpha _A : F(A) \to G(A)\). Then, \(\alpha _A \circ \beta _A = (\alpha \circ \beta )_A = (1_G)_A = 1_{G(A)}\). Simmilarly, one can prove \(\beta _A \circ \alpha _A = 1_{F(A)}\). Hence, \(\alpha _A\) is an isomorphism.

Now, suppose it’s an isomorphism for all \(A \in \cat{A}\). Define \(\beta : G \to F\) as the natural transformation

suth that for all \(A \in \cat{A}\), \(\beta _A\) is the inverse of \(\alpha _A\).

We need to check that \(\beta \) is indeed a natural transformation. For this, take \(A, A' \in \cat{A}\) and

\(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\).

Then, since \(\alpha \) is a natural transformation, we have \(\alpha _{A'} \circ F(f) = G(f) \circ \alpha _A\). Composing with \(\beta _A\) on the RHS

and \(\beta _{A'}\) on the LHS we get

\begin{align*} \beta _{A'} \circ (\alpha _{A'} \circ F(f)) \circ \beta _A & = \beta _{A'} \circ (G(f) \circ \alpha _A) \circ \beta _A \\ (\beta _{A'} \circ \alpha _{A'}) \circ F(f) \circ \beta _A & = \beta _{A'} \circ G(f) \circ (\alpha _A \circ \beta _A) \\ 1_{F(A')} \circ F(f) \circ \beta _A & = \beta _{A'} \circ G(f) \circ 1_{G(A)} \\ F(f) \circ \beta _A & = \beta _{A'} \circ G(f) \end{align*}

Hence, \(\beta \) is a natural transformation, as desired.

Also, \((\alpha \circ \beta )_A = \alpha _A \circ \beta _A = 1_{G(A)}\). Simmilarly, \((\beta \circ \alpha )_A = 1_{F(A)}\). This means that \(\alpha \circ \beta = 1_G\) and \(\beta \circ \alpha = 1_F\). \(\blacksquare \)

Definition 4.9. Given functors \(F, G : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\), we say that

\(F(A) \cong G(A)\) naturally in \(A\)

if \(F\) and \(G\) are naturally isomorphic.

The motivation for this alternative terminology is that if \(F(A) \cong G(A)\) naturally in \(A\), then \(F(A) \cong G(A)\)

for all \(A \in \catobj{A}\). But more is true: we can choose isomorphisms \(\alpha _A : F(A) \to G(A)\) s.t. \(\alpha \) is a natural

transformation.

Example 4.10. Let \(F, G\) be functors from a discrete category \(\cat{A}\) to \(\cat{B}\). Then, \(F \cong G\) iff \(F(A) \cong G(A)\) for

all \(A \in \cat{A}\)

Proof

Suppose \(F \cong G\). Then, \(\alpha \circ \beta = 1_G\) and \(\beta \circ \alpha = 1_F\) for some natural transformation \(\beta : G \to F \). Notice that \(\alpha _A : F(A) \to G(A)\) in an

isomorphism with inverse \(\beta _A : G(A) \to F(A)\).

Now, suppose \(F(A) \cong G(A)\) for all \(A \in \cat{A}\). For each \(A\), let \(\alpha _A : F(A) \to G(A)\) be an isomorphism and \(\beta _A : G(A) \to F(A)\) its inverse. Then, \(\alpha \)

and \(\beta \) are both natural transformations.

Indeed, let \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}\) and \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\). Since \(\cat{A}\) is discrete, the non-emptiness of \(\catmor{A}{A}{A'}\) implies \(A=A'\), \(f=1_{A}\). This means

that \(F(f)=1_{F(A)}\) and \(G(f)=1_{G(A)}\). So we have \(\alpha _{A'} \circ F(f) = \alpha _{A} \circ 1_{F(A)}\) \(= \alpha _A = 1_{G(A)} \circ \alpha _A = G(f) \circ \alpha _A\) so that \(\alpha \) is a natural transformation. One can prove that \(\beta \) is

also a natural transformation. \(\blacksquare \)

Example 4.11. Let \(\textbf{FDVect}\) be the category of finite-dimensional vector spaces over

some field \(K\). The dual vector space construction on Remark 3.7 defines a

contravariant functor from \(\textbf{FDVect}\) to itself.

We have two different ways of treating a contravariant functor as a covariant

one. Using both of these ways, the double dual functor \((-)^{**}\) is a (covariant) functor

from \(\textbf{FDVect}\) to itself. Another functor from \(\textbf{FDVect}\) to itself is the identity one. It just so

happens that there is a natural isomorphism between these two functors. Can

you prove it?

Proof

Define the natural transformation \(\pi : 1_{\textbf{FDVect}} \to (-)^{**}\) as follows. For each \(V \in \textbf{FDVect}\), \(\pi _V\) is the morphism which

takes some \(v \in V\) to the map which takes \(\varphi \in V^*\) to \(\varphi (v)\). Using standard linear algebra, we now that

when we see \(\pi _V\) as a linear transformation, it’s isomorphic. Using this fact, it’s not hard

to show that \(\pi \) is a natural transformation. Also, using lemma

4.8, we can prove that \(\pi \)

is a natural isomorphism.

\(\blacksquare \)

Remark 4.12. By the language of definition 4.9, we can say that \(V \cong V^{**}\) naturally in

\(V\).

This formalizes the idea that the double dual construction is a natural, or

canonical one. You don’t need to choose anything to define it. It’s not just that

we can define a linear isomorphism \(V \to V^{**}\) for each \(V\), but that we can do so in a way

that respects the structure of the category of vector spaces. Although \(V^{*}\) is linearly

isomorphic to \(V\), this isomorphism is not ”natural” at all. It depends on the choice

of an arbitrary basis for \(V\).

The concept of natural isomorphism leads to another question. You see, we can

think of two objects as ”the same” when there’s an isomorphism between them. We

can think of functors as ”the same” when there’s a natural isomorphism

between them. But when are categories ”the same”? Imposing that they

must be isomorphic when seen as objects of \(\textbf{CAT}\) is unreasonably strict. This is

because if \(\cat{A} \cong \cat{B}\), there exist functors \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) and \(G : \cat{B} \to \cat{A}\) such that \(G \circ F = 1_{\cat{A}}\) and \(F \circ G = 1_{\cat{B}}\). But equality between

functors is too strict, because, as I’ve just stated, the ideal notion of equality

between functors should be natural isomorphism. This leads to the following

definition

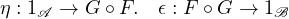

Definition 4.13. An equivalence between categories \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) consists of a pair of

functors \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) and \(G : \cat{B} \to \cat{A}\) together with natural isomorphisms

If there exists an equivalence between \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\), we say that \(\cat{A}\) and \(\cat{B}\) are equivalent,

and write \(\cat{A} \simeq \cat{B}\). We also say that \(F\) and \(G\) are equivalencies.

Definition 4.14. A functor \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) is essentially surjective on objects if for all \(B \in \cat{B}\), there

exists \(A \in \cat{A}\) such that \(F(A) \cong B\).

Proposition 4.15. A functor is an equivalence if and only if it is full, faithfull

and essentially surjective on objects.

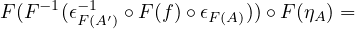

Proof

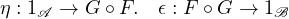

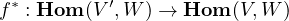

Let \(F : \cat{A} \to \cat{B}\) be an equivalence. Then, there exists \(G : \cat{B} \to \cat{A}\) and natural isomorphisms \(\eta : 1_{\cat{A}} \to G \circ F\) and \(\epsilon : F \circ G \to 1_{\cat{B}}\).

Then:

-

1.

- \(F\) is full:

Let \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}\) and \(g \in \catmor{B}{F(A)}{F(A')}\). Then \(G(g) \in \catmor{A}{G(F(A))}{G(F(A'))}\). Also, \(\eta _A\) and \(\eta _{A'}\) are isomorphisms from \(A\) to \(G(F(A))\) and from \(A'\) to \(G(F(A'))\),

respectively.

This means that \(F(\eta _A)\) and \(F(\eta _{A'})\) are isomorphisms from \(F(A)\) to \(F(G(F(A)))\) and from \(A'\) to \(F(G(F(A')))\),

respectively. Moreover, \(\epsilon _{F(A)}\) and \(\epsilon _{F(A')}\) are isomorphisms from \(F(G(F(A)))\) to \(F(A)\) and from \(F(G(F(A')))\) to \(F(A')\),

respectively. We’ve already proved that isomorphisms are unique. So we

must have \(\epsilon _{F(A)} = F(\eta _A)^{-1}\) and \(\epsilon _{F(A')} = F(\eta _{A'})^{-1}\).

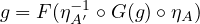

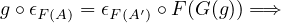

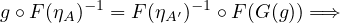

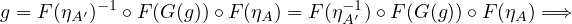

By the naturality of \(\epsilon \), we have

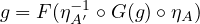

this means that we’ve found an \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\) such that \(F(f) = g\), namely \(f = \eta _{A'}^{-1} \circ G(g) \circ \eta _{A}\).

this means that we’ve found an \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\) such that \(F(f) = g\), namely \(f = \eta _{A'}^{-1} \circ G(g) \circ \eta _{A}\).

-

2.

- \(F\) is faithfull:

Let \(A, A' \in \catobj{A}\) and \(f_1, f_2 \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\) such that \(F(f_1) = F(f_2)\). Using the naturality of \(\eta \), we have \(G(F(h)) \circ \eta _A = \eta _{A'} \circ h\) for all \(h \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\). In particular,

if \(h=f_i\), then, since \(\eta _{A'}\) is an isomorphism: \(f_i = \eta _{A'}^{-1} \circ G(F(f_i)) \circ \eta _A\). But the RHS is the same for \(i=1,2\), which

means \(f_1 = f_2\).

-

3.

- \(F\) is essentially surjective on objects:

Let \(B \in \catobj{B}\). Then, \(F(G(B)) \cong B\) by the isomorphism \(\epsilon _B\). So we’ve found an \(A \in \catobj{A}\) such that \(F(A) \cong B\), namely

\(A=G(B)\).

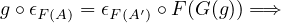

Conversely, suppose that \(F\) if full, faithfull and essentially surjective on objects.

We need to find a functor \(G : \cat{B} \to \cat{A}\) and natural isomorphisms \(\eta : 1_{\cat{A}} \to G \circ F\) and \(\epsilon : F \circ G \to 1_{\cat{B}}\) to finish our

proof.

Since \(F\) is essentially surjective on objects, for each \(B \in \cat{B}\), we can find some \(A \in \cat{A}\) such that \(F(A) \cong B\).

We can define \(G(B)\) to be this \(A\) (there may be multiple \(A\), but I don’t care). Trivially, \(F(G(B)) \cong B\) for all

\(B \in \cat{B}\). Call this isomorphism from \(F(G(B))\) to \(B\) \(\epsilon _B\).

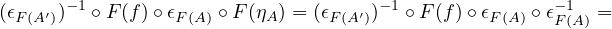

Also, for each \(B, B' \in \cat{B}\) and \(g \in \catmor{B}{B}{B'}\), consider the morphism \(\epsilon _{B'}^{-1} \circ g \circ \epsilon _B\). It is a morphism from \(F(G(B))\) to \(F(G(B'))\). Due to

the faithfullness and fullness of \(F\) when applied to the map from \(\catmor{A}{G(B)}{G(B')}\) to \(\catmor{B}{F(G(B))}{F(G(B'))}\), we can find a

unique \(h \in \catmor{A}{G(B)}{G(B')}\) such that \(F(h) = \epsilon _{B'}^{-1} \circ g \circ \epsilon _B\). Define \(G(g) = h\). We can also write this as \(G(g) = F^{-1}(\epsilon _{B'}^{-1} \circ g \circ \epsilon _B)\). Then, \(G\) is a functor from \(\cat{B}\) to

\(\cat{A}\).

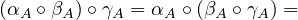

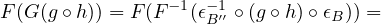

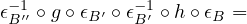

Indeed, if \(B \in \cat{B}\), then \(G(1_B) = F^{-1}(\epsilon _B^{-1} \circ 1_B \circ \epsilon _B)\) \(= F^{-1}(1_{F(G(B))}) = 1_{G(B)}\). Also, if \(B, B', B'' \in \cat{B}\) and \(g \in \catmor{B}{B'}{B''}\), \(h \in \catmor{B'}{B}{B'}\), then

Since \(F\) is full and faithfull, we have \(G(g \circ h) = G(g) \circ G(h)\).

So \(G\) is indeed a functor. Also, \(\epsilon \) is a natural isomorphism. We’ve already checked

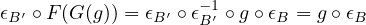

that \(\epsilon _B\) is an isomorphism. Now it remains to check its naturality. Indeed, let \(B, B' \in \cat{B}\) and \(g \in \catmor{B}{B}{B'}\).

Then, we have

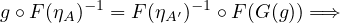

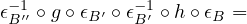

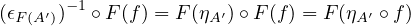

Simmilarly, we can define \(\eta \) in the following way. Since \(\epsilon _{F(A)}^{-1}\) is an isomorphism from \(F(A)\) to

\(F(G(F(A)))\), we can just take \(\eta _A = F^{-1}(\epsilon _{F(A)}^{-1})\). We have \(F(\eta _A \circ F^{-1}(\epsilon _{F(A)})) = \epsilon _{F(A)}^{-1} \circ \epsilon _{F(A)} = 1_{F(G(F(A)))}\) and \(F(F^{-1}(\epsilon _{F(A)}) \circ \eta _A) = \epsilon _{F(A)} \circ \epsilon _{F(A)}^{-1} = 1_{F(A)}\) so that \(\eta _A \circ F^{-1}(\epsilon _{F(A)}) = 1_{G(F(A))}\) and \(F^{-1}(\epsilon _{F(A)}) \circ \eta _A = 1_A\). This proves that \(\eta \) is an

isomorphism.

Now, let \(A, A' \in \cat{A}\) and \(f \in \catmor{A}{A}{A'}\). Then,

So the naturality of \(\eta \) follows from the fullness and faithfullness of \(F\). \(\blacksquare \)

Corollary 4.16. Let \(F : \cat{C} \to \cat{D}\) be a full and faithfull functor. Then \(\cat{C} \simeq \cat{C}'\), the subcategory of

\(\cat{D}\) whose objects are isomorphic to \(F(C)\) for some \(C \in \cat{C}\).

Proof

By the definition of subcategory, one also needs to make explicit the subset of

morphisms. When it is omitted, you may assume that it is equal to that of the

”super” category.

Let \(F' : \cat{C} \to \cat{C}'\) defined by \(F'(C) = F(c)\), \(F'(f) = F(f)\). Then, \(F'\) is clearly a functor. Moreover, it is essentially surjective

on objects. Since \(F'\) is additionally full and faithfull (which is inherited from \(F\)), then by

the previous proposition, \(\cat{C} \simeq \cat{C}'\). \(\blacksquare \)

Example 4.17. Let \(\cat{A}\) be any category and \(\cat{B}\) a full subcategory of \(\cat{A}\) with at least

one object from each isomorphism class of \(\cat{A}\). Then, the inclusion functor \(\cat{B} \to \cat{A}\) is full,

faithfull and essentially surjective on objects. So \(\cat{B} \simeq \cat{A}\).

Example 4.18. Let \(\textbf{FinSet}\) denote the category of finite sets and functions between

them. Let \(\cat{B}\) be a subcategory of it whose objects are \(\textbf{0}, \textbf{1}, \textbf{2}, \dots \) where \(\textbf{n}\) is an arbitrary

chosen set with \(n\) elements. Then, by the previous example, \(\cat{B} \simeq \textbf{FinSet}\).

Exercise 4.19. Let \(\cat{C}\) be the subcategory of \(\textbf{CAT}\) whose objects are the categories

with exactly one object. Then, \(\cat{C} \simeq \textbf{Mon}\).

Proof

Come on I won’t do everything for you. \(\blacksquare \)