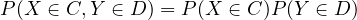

Definition 2.2. Two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent if for all \(C, D \in \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}}\),

This is the second blog post of a series of blog posts about measure theoretic probability.

Every post is heavily based on Rick Durrett’s book “Probability: Theory and Examples”, but I’ll occasionally drop some of my own ideas/some stuff I find online.

Also, each post is more of a summary of the book than actual detailed notes. I’ll be updating it as I learn more.

Let \((\Omega , \mathcal{F}, P)\) be a probability space.

Definition 2.1. Two events (elements of \(\mathcal{F}\)) \(A\) and \(B\) are independent if \(P(A \cap B) = P(A) P(B)\).

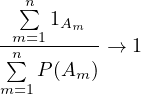

Definition 2.2. Two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent if for all \(C, D \in \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}}\),

Definition 2.3. Two (sub)\(\sigma \)-algebras (of \(\mathcal{F}\)) \(\mathcal{F}_1\) and \(\mathcal{F}_2\) are independent if for all \(A \in \mathcal{F}_1\) and \(B \in \mathcal{F}_2\), the events \(A\) and \(B\) are independent.

The second definition is a special case of the third (in the sense that \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent iff \(\sigma (X)\) and \(\sigma (Y)\) are independent):

Hence, it is sufficient to prove that the sets \(X^{-1}(B)\) and \(Y^{-1}(C)\) are independent for all \(B,C \in \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}}\).

But this is immediate from the definition of independent random variables.

\(\blacksquare \)Proof

The first definition is, in turn, a special case of the second (in the sense that \(A\) and \(B\) are independent iff \(1_A\) and \(1_B\) are independent):

More generally, we can define independence for more than two events, r.v.’s, or \(\sigma \)-algebras.

Definition 2.6. \(\sigma \)-algebras \(\mathcal{F}_1, \mathcal{F}_2, \ldots , \mathcal{F}_n\) are independent if whenever \(A_i \in \mathcal{F}_i\) for \(i = 1, \ldots , n\), we have

\[ P\left (\bigcap _{i=1}^n A_i\right ) = \prod _{i=1}^n P(A_i) \]

Random variables \(X_1, \ldots , X_n\) are independent if whenever \(B_i \in \mathcal{B}_\mathbb{R}\) for \(i = 1, \ldots , n\), we have \[ P\left (\bigcap _{i=1}^n X_i^{-1}(B_i)\right ) = \prod _{i=1}^n P(X_i \in B_i) \]

Sets \(A_1, \ldots , A_n\) are independent if whenever \(I \subset \{1, \ldots , n\}\), we have \[ P\left (\bigcap _{i \in I} A_i\right ) = \prod _{i \in I} P(A_i) \]

You may think this last definition looks ”too different” from the others. However, it is perfectly fine:

Theorem 2.10. Events \(A_1, \dots , A_n\) are independent iff \(1_{A_1}, \dots , 1_{A_n}\) are independent.

Theorem 2.11. Random variables \(X_1, \dots , X_n\) are independent iff \(\sigma (X_1), \dots , \sigma (X_n)\) are independent.

Definition 2.13. Events \(A_1, A_2, \dots \) are independent if for all finite positive integer sequence \(s_1, \dots , s_n\) the events \(A_{s_1}, \dots , A_{s_n}\) are independent. We define independece for random variables and sigma algebras analogously.

Theorem 2.14. Events \(A_1, A_2, \dots \) are independent iff r.v.’s \(1_{A_1}, 1_{A_2}, \dots \) are independent.

Theorem 2.15. Random variables \(X_1, X_2, \dots \) are independent iff \(\sigma (X_1), \sigma (X_2), \dots \) are independent.

Collections of sets \(\mathcal{A}_1, \dots , \mathcal{A}_n \subset \mathcal{F}\) are said to be independent if whenever \(A_i \in \mathcal{A}_i\) and \(I \subset \{1, \dots , n\}\) we have \(P(\cap _{i \in I} A_i) = \prod _{i \in I} P(A_i)\). We define independence for a countable collection of subsets of \(\mathcal{F}\) the same way we did in the previous subsection.

Remark 2.17. If \(\mathcal{A}_i = \{A_i\}\) this is the same as independence for events.

If each of the \(\mathcal{A}_i\) is a sub-\(\sigma \)-algebra of \(\mathcal{F}\), this is the same as independence for \(\sigma \)-algebras.

Definition 2.19. \(\mathcal{A} \subset \mathcal{P}(\Omega )\) is a \(\pi \)-system if it is non-empty and closed under (finite) intersection.

Definition 2.20. \(\mathcal{L} \subset \mathcal{P}(\Omega )\) is a \(\lambda \)-system if

Theorem 2.21 (Dynkin’s \(\pi \)-\(\lambda \) theorem). If \(\mathcal{P}\) is a \(\pi \)-system and \(\mathcal{L}\) is a \(\lambda \)-system that contains \(\mathcal{P}\) then \(\sigma (\mathcal{P}) \subset \mathcal{L}\).

Theorem 2.22. Suppose \(\mathcal{A}_1, \dots , \mathcal{A}_n\) are independent and each of them is a \(\pi \)-system. Then \(\sigma (\mathcal{A}_1), \dots , \sigma (\mathcal{A}_n)\) are independent.

Corollary 2.23. The same holds for a countable sequence of independent \(\pi \)-systems \(\mathcal{A}_1, \mathcal{A}_2, \dots \).

Corollary 2.24. Theorem 2.22 holds for any countable set of random variables (the product may be infinite).

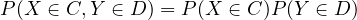

Theorem 2.25. In order for \(X_1, \dots , X_n\) to be independent, it is sufficient that for all \(x_i \in (-\infty , \infty ]\).

Proof

Theorem 2.26. Suppose \(\mathcal{F}_{i, j}\), \(1 \leq i \leq n\), \(1 \leq j \leq m(i)\) are independent sub-\(\sigma \)-algebras of \(\mathcal{F}\) and let \(\mathcal{G}_i = \sigma (\cup _j \mathcal{F}_{i, j})\). Then \(\mathcal{G}_1, \dots , \mathcal{G}_n\) are independent.

Proof

Corollary 2.27. The previous theorem holds for a countable number of families \(\sigma \)-algebras, each with a countable number of members.

Theorem 2.28. if for \(1 \leq i \leq n\), \(1 \leq j \leq m(i)\), \(X_{i, j}\) are independent and \(f_i : \mathbb{R}^{m(i)} \to \mathbb{R}\) are measurable then \(f_i(X_{i, 1}, \dots , X_{i, m(i)})\) are independent.

Let \(V_i\) denote the random vector \((X_{i, 1}, \dots , X_{i, m(i)})\) and \(S_i =\) sets of the form \(\{ \omega : V_i \in A_1 \times \dots \times A_{m(i)} \}\) where each \(A_j\) is Borel. Notice

that the sets of the form \(A_1 \times \dots \times A_{m(i)}\) generate \(R^{m(i)}\). This means that \(\sigma (S_i)\) is precisely the smallest

\(\sigma \)-algebra that makes \(V_i\) measurable i.e. \(\sigma (S_i) = \sigma (V_i)\).

Also, notice that \(\{ \omega : V_i \in A_1 \times \dots \times A_{m(i)} \} =\) \(\{\omega : \forall 1 \leq j \leq m(i), X_{i,j} \in A_j \} = \) \(\cap _j X_{i, j}^{-1}(A_j) \). Since each element of this intersection belongs to \(\mathcal{G}_i\), we have \(S_i \subset \mathcal{G}_i\),

hence \(\sigma (S_i) \subset \mathcal{G}_i\).

This means that \(G_i = f_i(X_{i, 1}, \dots , X_{i, m(i)})\) is \(\mathcal{G}_i\) measurable, because if \(B_1 \in \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}}\), then \(f_i^{-1}(B_1) = B_2 \in \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}^{m(i)}}\). Now, \(V_i^{-1}(B_2) \in \sigma (V_i) = \sigma (S_i)\). Therefore,

\(G_i^{-1}(B_1) \in \mathcal{G}_i\).

Since each \(G_i\) is \(\mathcal{G}_i\) measurable, we have \(\sigma (G_i) \subset \mathcal{G}_i\). So by the last theorem, the \(\mathcal{G}_i\) are

independent. Therefore, the \(\sigma (G_i)\) are also independent and hence the \(G_i\) are independent.

\(\blacksquare \)Proof

Corollary 2.29. The previous theorem also applies to a countable set of finite families of random variables.

Theorem 2.30. If \(X_1, \dots , X_n\) are random variables and \(X_i\) has distribution \(\mu _i\), then \((X_1, \dots , X_n)\) has distribution \(\mu _1 \times \dots \times \mu _n\).

Theorem 2.31. Suppose \( X \) and \( Y \) are independent and have distributions \( \mu \) and \( \nu \). If \( h : \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R} \) is a measurable function with \( h \geq 0 \) or \( E|h(X, Y)| < \infty \), then \[ E h(X, Y) = \int \int h(x, y) \, \mu (dx) \, \nu (dy). \]

In particular, if \( h(x, y) = f(x) g(y) \) where \( f, g : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) are measurable functions with \( f, g \geq 0 \) or \( E|f(X)| \) and \( E|g(Y)| < \infty \), then \[ E f(X) g(Y) = E f(X) \cdot E g(Y). \]

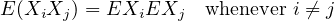

Theorem 2.32. If \( X_1, \dots , X_n \) are independent and have (a) \( X_i \geq 0 \) for all \( i \), or (b) \( E|X_i| < \infty \) for all \( i \), then \[ E \left ( \prod _{i=1}^n X_i \right ) = \prod _{i=1}^n E X_i \] i.e., the expectation on the left exists and has the value given on the right.

Definition 2.33. Two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) with \(EX^2 < \infty \), \(EY^2 < \infty \) that have \(E(XY)=EXEY\) are said to be uncorrelated. The finite second moments are needed so that we know \(E|XY| < \infty \) by the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality.

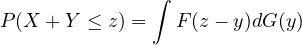

Theorem 2.34. If \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent, \(F(x) = P(X \leq x)\), and \(G(y) = P(Y \leq y)\), then

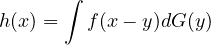

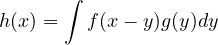

Theorem 2.35. Suppose that \(X\) with density \(f\) and \(Y\) with distribution function \(G\) are independent. Then \(X+Y\) has density

Example 2.36. The gamma density with parameters \( \alpha \) and \( \lambda \) is given by \[ f(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{\lambda ^\alpha x^{\alpha -1} e^{-\lambda x}}{\Gamma (\alpha )} & \text{for } x \geq 0, \\ 0 & \text{for } x < 0, \end{cases} \] where \( \Gamma (\alpha ) = \int _0^\infty x^{\alpha -1} e^{-x} \, dx \).

Theorem 2.37. If \( X = \text{gamma}(\alpha , \lambda ) \) and \( Y = \text{gamma}(\beta , \lambda ) \) are independent, then \( X + Y \) is \( \text{gamma}(\alpha + \beta , \lambda ) \). Consequently, if \( X_1, \dots , X_n \) are independent exponential(\( \lambda \)) random variables, then \( X_1 + \cdots + X_n \) has a gamma(\( n, \lambda \)) distribution.

Example 2.38. Normal density with mean \(\mu \) and variance \(\sigma ^2\): \[ (2\pi \sigma ^2)^{-1/2} \exp \left (-\frac{(x - \mu )^2}{2\sigma ^2}\right ). \]

Theorem 2.39. If \(X \sim \operatorname{normal}(\mu , a)\) and \(Y \sim \operatorname{normal}(\nu , b)\) are independent then \(X + Y \sim \operatorname{normal}(\mu + \nu , a + b)\).

It’s easy to construct \(n\) independent random variables \(X_1, \dots , X_n\) with \(n\) given distribution functions \(F_1(x)\), \( \dots , F_n(x)\). We can just take \(\Omega = \mathbb{R}^n\), \(\mathcal{F} = \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}^n}\) and \(P\) such that

![P ((a1,b1]× ⋅⋅⋅× (an,bn ]) = (F1(b1)− F1(a1))⋅⋅⋅⋅⋅(Fn(bn) − Fn (an))](chap2-measure-theoretic-probability6x.png)

(more precisely, \(P = \mu _1 \times \mu _n\))

But our procedure of constructing product measures fails when we want to construct infinitely many independent random variables. In other words, we can’t just take \(\Omega = \mathbb{R}^\infty \), \(\mathcal{F} = \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}^\infty }\) and \(P = \mu _1 \times \mu _2 \times \dots \).

To do that, we need a stronger result

Theorem 3.1 (Kolmogorov’s Extension Theorem). Suppose we are given probability measures \(\mu _n\) on \((\mathbb{R}^n, \mathcal{B}_{\mathbb{R}^n})\) that are consistent, that is,

![μn+1((a1,b1]× ⋅⋅⋅× (an,bn]× ℝ) = μn((a1,b1]× ⋅⋅⋅× (an,bn])](chap2-measure-theoretic-probability7x.png)

![P ({ω : ωi ∈ (ai,bi],1 ≤ i ≤ n}) = μn((a1,b1]× ⋅⋅⋅× (an,bn])](chap2-measure-theoretic-probability8x.png)

Definition 3.2. \((S, \mathcal{S})\) is said to be a standard Borel space if there is a \(1-1\) map \(\varphi \) from \(S\) into \(\mathbb{R}\) so that \(\varphi \) and \(\varphi ^{-1}\) are both measurable.

Theorem 3.3. If \(S\) is a Borel subset of a complete separable metric space \(M\), and \(\mathcal{S}\) is the collection of Borel subsets of \(S\), then \((S, \mathcal{S})\) is a standard Borel space.

Definition 4.1. \(Y_n\) converges in probability to \(Y\) if for all \(\epsilon > 0\), \(P(|Y_n - Y| > \epsilon ) \to 0\) as \(n \to \infty \).

A family of random variables \(X_i\) (\(i \in I\)) with \(EX_i^2 < \infty \) is said to be uncorrelated if we have

Theorem 4.5 (\(L^2\) weak law). Let \(X_1, X_2, \dots \) be uncorrelated random variables with \(EX_i = \mu \) and \(\operatorname{var}(X_i) \leq C < \infty \). If \(S_n = X_1 + \dots + X_n\) then as \(n \to \infty \), \(S_n/n \to \mu \) in \(L^2\) and in probability.

Definition 4.6. When \(X_1, X_2, \dots \) are all independent random variables with the same distributon, we say they’re independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.).

It’s possible to prove some interesting things with probability.

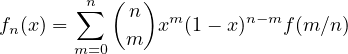

Example 4.7 (Polynomial approximation). Let \(f\) be a continuous function on \([0, 1]\), and let

![sup |fn(x|− f(x)| → 0

x∈[0,1]](chap2-measure-theoretic-probability12x.png)

Example 4.8 (A high-dimensional cube is almost the boundary of a ball). Let \(A_{n, \varepsilon } = \{x \in \mathbb{R}^n : (1 - \varepsilon ) \sqrt{n/3} < |x| < (1 + \varepsilon ) \sqrt{n/3} \}\). Then for any \(\varepsilon > 0\), \(|A_{n, \varepsilon } \cap (-1, 1)^n| / 2^n \to 1\).

Many classical limit theorems in probability concern arrays \(X_{n, k}\) of random variables and investigate their limiting behavior of the row sums \(S_n = X_{n, 1} + \dots + X_{n, n}\). In most cases, we assume that the random variables on each row are independent.

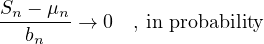

Theorem 4.9. (Here \(X_{n, 1}, \dots , X_{n, n}\) can be any sequence of random variables) Let \(\mu _n = ES_n\), \(\sigma _n^2 = \operatorname{var}(S_n)\). If \(\sigma _n^2/b_n^2 \to 0\) then

To extend the weak law to random variables without a second moment, we will truncate and then use Chebyshev’s inequality.

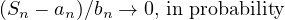

Theorem 4.11 (Weak law for triangular arrays). For each \(n\), let \(X_{n, k}\) (\(1 \leq k \leq n\)) be independent. Let \(b_n > 0\) with \(b_n \to \infty \), and let \(\overline{X}_{n, k} = X_{n, k} 1_{(|X_{n, k}| \leq b_n)}\). Suppose that as \(n \to \infty \)

If we let \(S_n = X_{n, 1} + \dots + X_{n, n}\) and put \(a_n = \sum _{k=1}^n E \overline{X}_{n, k}\), then

Theorem 4.12 (Weak law of large numbers). Let \(X_1, X_2, \dots \) be i.i.d. with

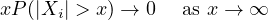

Remark 4.14. Taking \(p = 1 - \varepsilon \) here shows that \(xP(|X_1| > x) \to 0\) implies \(E|X_1|^{1- \varepsilon } < \infty \). This means that the assumption made in the previous theorem is not much weaker than finite mean.

Theorem 4.15. Let \(X_1, X_2, \dots \) be i.i.d. with \(E|X_i| < \infty \) and let \(S_n = X_1 + \dots + X_n\) and let \(\mu = EX_1\). Then \(S_n/n \to \mu \) in probability.

Notice that

Exercise 5.1. Prove that \(P(\limsup A_n) \geq \limsup P(A_n)\) and \(P(\liminf A_n) \leq \liminf P(A_n)\).

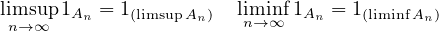

Definition 5.2. It is common to write \(\limsup A_n = \{ \omega : \omega \in A_n \text{ i.o.} \}\) where i.o. means infinitely often.

Theorem 5.3 (Borel-Cantelli lemma). If \(\sum _{n=1}^\infty P(A_n) < \infty \) then \(P(A_n \text{ i.o.}) = 0\) (in the sense of \(P(\limsup A_n)=0\)).

Theorem 5.4. \(X_n \to X\) in probability iff for every subsequence \(X_{n(m)}\) there is a further subsequence \(X_{n(m_k)}\) that converges a.s. to \(X\).

Theorem 5.5. If \(f\) is continuous and \(X_n \to X\) in probability then \(f(X_n) \to f(X)\) in probability. If, in addition, \(f\) is bounded then \(Ef(X_n) \to Ef(X)\).

Our first law of large numbers tells us:

Theorem 5.6. If \(X_1, X_2, \dots \) are i.i.d. with \(EX_i \to \mu \) and \(EX_i^4 < \infty \) and \(S_n = X_1 + \dots + X_n\) then \(S_n/n \to \mu \) a.s.

Theorem 5.7 (The second Borel-Cantelli lemma). If the events \(A_n\) are independent then \(\sum P(A_n) = \infty \) implies \(P(\limsup A_n) = 1\).

Theorem 5.8. If \(X_1, X_2, \dots \) are i.i.d. with \(E|X_i| = \infty \), then \(P(|X_n| \geq n \text{ i.o.}) = 1\). So if \(S_n = X_1 + \dots + X_n\) then \(P(\lim S_n/n \text{ exists and } \in (-\infty , \infty )) = 0\).

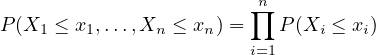

Theorem 5.9. If \(A_1, A_2, \dots \) are pairwise independent and \(\sum _{n=1}^\infty P(A_n) = \infty \), then as \(n \to \infty \)